"Who are you wearing?” That has been the perennial question on the red carpet for the past two decades, as reporters asked stars about their dresses, beauty routines and exercise regimes. But at the 2018 Golden Globes, the phrase rang hollow. Following the Harvey Weinstein scandal and the launch of Time’s Up, more than 300 women in Hollywood had announced their intention to wear black to raise awareness for gender inequality. In response, E! Entertainment, the US network that has long been the home of red carpet reporting, announced they would be changing their signature question to “Why are you wearing black?”. When Ryan Seacrest posed this to Meryl Streep, who was attending with the activist Ai-jen Poo, she replied, “We feel emboldened in this moment to stand together in a thick black line dividing then from now.” Streep was presaging a new era for women in Hollywood, but also the beginning of the end for the red carpet as we know it.

Red carpets have a long and illustrious history. The earliest reference to one can be found in ancient Greece, with Aeschylus’s 458 BC play Agamemnonshowing a red carpet being rolled out for the eponymous king upon his return from the Trojan war. His wife Clytemnestra says, “step down from your chariot, and let not your foot, my lord, touch the earth.” He responds, “I am a mortal, a man; I cannot trample upon these tinted splendours without fear thrown in my path.” Even then, the red carpet was hallowed ground – it had the power to elevate mere mortals into deities.

During the Renaissance, red carpets were reserved for throne rooms due to the high cost of scarlet cochineal dyes. One was used in 1821 to welcome US president James Monroe ashore in South Carolina, while in 1902, the New York Central Railroad used them to direct passengers onto their 20th Century Limited train. It wasn’t until 1922, at the premiere of Douglas Fairbanks’ Robin Hood, that movie stars first walked the red carpet. The Oscars adopted them in 1961, the ceremony was first televised in 1964, and thus the red carpet parade as we recognise it today was born.

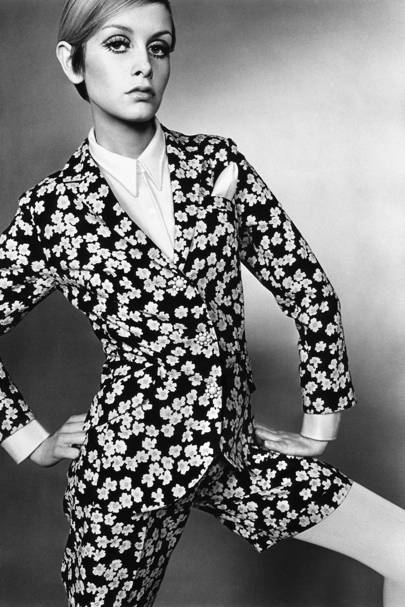

Footage from the 1964 Oscars shows fans screaming with delight at the arrival of Julie Andrews and Gregory Peck, before the stars are quickly shuffled into the auditorium. It would take another 30 years for interviews, camera crews and live coverage to become de rigueur. At the forefront of this new trend was Joan Rivers, who first hosted E!’s Golden Globes pre-show in 1994. Her acerbic wit was a hit with viewers, particularly at a time when red carpet fashion was becoming more outlandish Céline Dion wore a backwards Dior tuxedo to the Oscars in 1999; Björk showcased her swan dress in 2001). 1998, the year that Titanic took home the award for Best Picture, was a high-water mark for TV ratings, with the Oscars ceremony garnering 57 million viewers. By this point, Rivers’ pre-show was so popular that the network doubled its running time to two hours.

Buoyed by this success, E! expanded its roster to include the post-awards special Fashion Police and added a host of new features to its red carpet coverage: the glam-360-cam, the clutch-cam, the stiletto-cam and the mani-cam. The latter, which involved a miniature red carpet on which actresses were asked to flaunt their fingers, provoked a swift backlash. At the 2014 Golden Globes, Elisabeth Moss told E!’s Giuliana Rancic, “There’s something I wanted to do last time but didn’t”, before giving a middle finger to the mani-cam. Her frustration was echoed by Cate Blanchett at the Screen Actors Guild Awards. When an E! camera scanned her body up and down, she peered into the lens and said, “Do you do that to the guys? What do you think is going to happen down there that’s so fascinating?”

The following year, Reese Witherspoon, Jennifer Anistonand Julianne Mooreall refused to put their fingers in the mani-cam at the SAG Awards. At the 2015 Baftas, Buzzfeed parodied these increasingly ridiculous red carpet interviews by asking men the same questions as women. This included requesting Eddie Redmayne to twirl for the camera, asking a bewildered Michael Keaton if he was wearing spandex and quizzing Weinstein himself about how long it had taken him to get ready. Public opinion was beginning to sour and E!’s ratings were plummeting. Following the death of Rivers in 2014, Fashion Police went on a five-month-long hiatus before being cancelled in 2017. Seacrest continues to host the pre-Oscars red carpet show, which this year averaged at 1.3 million viewers, a 43 per cent drop from last year. The audience for the Oscars ceremony also hit an all-time low in 2018, at 26.5 million.

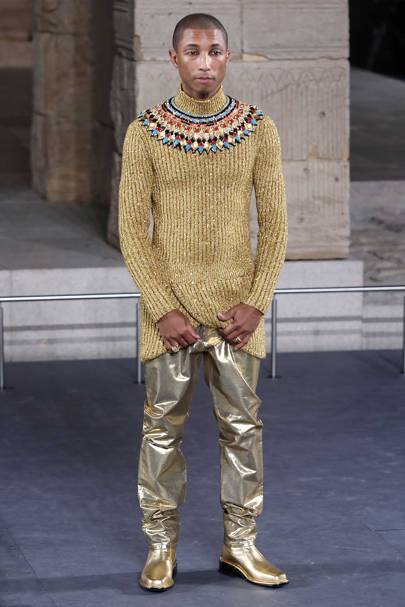

This decline of the red carpet coincided with an increasingly tense political landscape in the US. Donald Trump’s travel ban prompted several attendees of the 2017 Oscars, including Ruth Negga and Karlie Kloss, to wear blue ribbons on the red carpet in support of the American Civil Liberties Union. Meanwhile, Emma Stone had a Planned Parenthood pin fastened to her Givenchy couture gown. Resistance was more overt at the 2017 SAG Awards, where The Big Bang Theory actor Simon Helberg walked the red carpet with a sign that read “Refugees Welcome”.

It was with #MeToo and Time’s Up, however, that red carpet protests transformed from tacit non-compliance to out-and-out rebellion. A sea of women in black swept the Golden Globes like an unstoppable army, calling out the gender pay gap on the red carpet (Debra Messing criticised E! for failing to pay host Catt Sadler the same as her male co-presenter) and exposing the lack of female directors on the stage (Natalie Portmanintroduced the category by saying, “here are the all-male nominees”). The Baftas mirrored the all-black dress code, while the Grammys invited stars to wear white roses. But for the 2018 Oscars, Time’s Up announced there would be no dress code and no call to arms on the red carpet.

Some interpreted this as Hollywood’s return to business as usual, but the tectonic plates had already shifted. The red carpet hoop-jumping of previous years no longer felt like a requirement. The morning after the Oscars ceremony, Vanity Fair’s Hollywood correspondent Nicole Sperling noted the palpable change. “It felt kind of subdued,” she said, speaking on the magazine’s awards season podcast Little Gold Men. “A lot of people skipped the red carpet this year. Jordan Peele skipped it, Sam Rockwell skipped it – they took some photos and were escorted straight into the show. The publicists I spoke to said they just didn’t see the value in it anymore. I don’t know how this is going to proceed because there is that light, frothy red carpet that people like, but is that something we need? Is that a progressive part of our society?”

The women at the Cannes Film Festival certainly didn’t think so. In May, jury president Cate Blanchett led a rally on the red carpet arm in arm with 82 women – one for every female-directed film ever to have competed for the festival’s top prize in its 71-year history, compared to 1,645 films directed by men. Only one woman, Jane Campion, has ever won. Other injustices were also brought to light: 16 black actresses demonstrated against racism in the French film industry and co-authored a book entitled Black is Not My Job. A minute of silence was held on 15 May in honour of the 60 Palestinians killed by Israeli forces near the border between Gaza and Israel, with actress Manal Issa carrying a sign on the red carpet that read “Stop the attack on Gaza”. At a screening of The Dead and the Others, a film about northern Brazil’s indigenous Krahô community, placards demanded better treatment for the country’s native people.

Among the activism, jury member Kristen Stewartdominated headlines for taking off her Christian Louboutins at the premiere of BlacKkKlansman, defying Cannes’ heels-only policy. “There’s definitely a distinct dress code,” she told The Hollywood Reporter. “People get very upset if you don’t wear heels, but you can’t ask people to do that anymore. If you’re not asking guys to wear heels and a dress, you can’t ask me either.” Far from being empty gestures, the festival’s protests enacted policy change. A new charter for gender parity was signed at Cannes and has since been adopted by other leading film festivals including Venice and Toronto. The Cannes red carpet, which had once been Weinstein’s hunting ground, was slowly being reclaimed by women.

”I am heartened by the progress we’ve seen,” says Jennifer Siebel Newsom, founder of The Representation Project, whose #AskHerMore slogan has been gaining ground on the red carpet since its inception in 2014. “We’re hearing more questions asked of women beyond what they’re wearing, but that said, one important next step is amplifying other critical conversations like those raised by Time’s Up. We want to work alongside like-minded organisations with missions towards equal, diverse and gender-balanced representation in Hollywood and beyond.”

So, where does that leave us on the eve of 2019? The Toronto Film Festival and Emmy Awards passed largely without incident, though Planned Parenthood pins, ACLU ribbons and “I am a voter” badges nodded to the upcoming US midterms. Critics fear a slowdown at next year’s awards season, but that seems unlikely. The Golden Globes will follow the one-year anniversary of Time’s Up and once again no women have been nominated in the directing category. The 2019 Women’s March falls on 19 January, right between the Critics’ Choice Awards and the Producers Guild of America Awards. Just last week, Kevin Hart stepped down as Oscars host three days after being appointed, following controversy over perceived homophobic comments. Hollywood is as politically fraught as ever.

For now, the red carpet has survived, but its future depends on its willingness to adapt to changing times. Stylists, for whom it remains a lucrative enterprise, are wary of boycotts but recognise its need to change. “Of course it’s important,” says Elizabeth Saltzman, who dresses Saoirse Ronan and Gwyneth Paltrow. “But maybe it’s important in a different way. Maybe now we can use the red carpet to show people as they really are. Does it matter? Only as much as we all want it to. Is it the most important business? Well, it’s my business so it’s damn well important to me. I think there’s so much we can do with the red carpet, so let’s do it instead of giving up on it.” Will next season’s red carpet heed Saltzman’s words? We can only wait and see.