Michael was a production designer and art director who was able to tread seamlessly between the disciplines of fashion (he contributed to Vogue for over 25 years), theatre, ballet and film with a brilliance that enabled him to create some of the most spectacular and ambitious sets in these fields. “There are not enough adjectives to describe Michael,” said the costume designer Sandy Powell, as we both tried to make sense of a world that will no longer benefit from Michael’s brilliance and remarkable capacity for friendship and kindness.

I first came across Michael when I was a junior fashion writer at Harpers and Queen. I was in Paris for the shows, and a rusty key was the invitation to a Galliano show. The venue was a Hotel Particulier in the Marais behind a crumbling wall. We got there late, and weren’t allowed in by the security men, but climbed on a step and looked through the windows. We saw a staircase with dead leaves strewn down it, and a room filled with smoke. That was Michael, of course. Out of the smoke and down the stairs walked models dressed in bias cut black satin, lips painted aubergine and eyes lined in kohl. They were the most beautiful dresses I had ever seen, but the set, the absolute romance of it, that was what took my breath away.

A few years later I, along with my husband and some others, had started a festival in Cornwall, in the grounds of Port Eliot, where I lived for a while. We had done the sets for the first two festivals, but as the event grew, I felt I wanted us to do more with the stages. One day a close friend said, “You should talk to Michael Howells, he’d love you and Port Eliot.” We had lunch. The next weekend Michael was on a train to Cornwall. That first festival he made a stage which revolved. He would dress one side of the set and press and a button and spin it round. As the weekend progressed his sets got more elaborate with objects he had found in the house and the stage span faster and faster between each set change.

This was the beginning of a relationship with Port Eliot. Over time he became the creative director of the festival and worked with my late husband and I on the opening of the house to the public. A few years ago we gave him his 50th birthday party. A symbol of that party remains in the house to this day, a chandelier covered in blue hydrangeas and white feathers hangs in the drawing room and never fails to stop people in their tracks when they see it for the first time. It was so beautiful, we could not take it down after the party. Somehow Michael had managed to create something that absolutely fitted a room designed by John Soane in an ancient house in Cornwall. He gave it a modern note which did not jar. “Michael’s work at Port Eliot was such a symbol of success,” says Patrick Kinmonth, a fellow legendary production designer, art director and friend. “His relationship with the house and you and Peregrine and the spirit of that place, was a very beautiful thing. He took the house and only added and didn’t remotely take away from what was already there, he was so clever.”

During his time working at Port Eliot, Michael gathered around him an art department which comprised of god children, friends’ children and volunteers who camped beneath the big oak tree in the park. Along with his friends Sarah Husband, Carrie Lawson, Andy Tomlinson, Derek Brown, Alfie McHugh, Sarah Mower, Joseph Turnbull and Monty Richthofen, they created the look of the festival. We had no money and gave Michael virtually no budget, but it did not make any difference, in fact, he thrived on the challenge.

“You could give him a pile of elastic bands and paper clips and he would make something extraordinary,” says Sandy Powell. “Something you had never seen before. Out of pages from old books elephants’ heads, birds, a ball gown made entirely of paper for an imaginary ball at Manderley magically appeared." At the same time, he inspired the next generation and the one after that to get involved in production design. “He was literally like the Pied Piper,” says Hannah Rothschild, whose daughter worked on the festival in Michael’s art department. “He inspired people at every turn. He found reserves and talents in people they did not know they had.”

Ed Hall, theatre director, agrees: “There was no hierarchy in the work place with Michael. No fuss. No drama. All he was interested in was talent and hard work, and if you didn’t have talent but worked hard he would embrace you.” Michael worked with Hall on some of his most successful theatrical projects. “He did all the costumes on my Chariots of Fire. Not only were his costumes brilliant, but he was also an extraordinarily practical man. He worked out how to do an excess of 100 quick changes in the show. The thing ultimately about Michael is that he was a 360-degree artist. It is important the world remembers him like that. The world has to remember how talented he was.”

The writer and artist Jessica Berens adds: “On a personal level Michael always encouraged people to ask questions about established concepts and behave badly whenever possible." This, she believes, was particularly reflected in his work at the Port Eliot festival, where he started a flower show. “Michael believed great craft was produced in England at the folk level of Womens Institute events and summer fetes and that this craft risked being constricted by the sanitised ethos of the middle brow and Middle England. So, while working within the established criteria of the WI aesthetic he managed to encourage the presentation of wider ideas.” Thus, Berens knitted a giant terrorist for the scarecrow competition. “As an annual gallery of local artistry, it was a spectacular display of ideas worthy of anything displayed in contemporary galleries and far outreached what is expected of those who enter the traditional summer competitions of English tradition.” Yet at the same time no one could have loved English tradition more than Michael. Indeed, he said recently that if he won the lottery, “I would go round restoring the village halls in England because villages have lost their heart and sense of community and if they had village halls it might bring it back.”

At the same time, Michael loved excess. In Spain on a film, Kitty Arden, his floral collaborator for 44 years asked him, “How is your Spanish?”. Michael replied, “'Mas lentequelles por favor’ is all I need.” “More sequins please”. “He managed to do opulence without it turning into a hot mess. Without going too far,” says Sandy Powell. “All those Dior and Galliano shows, there was a lot going on in his sets and a lot going on with the dresses, but it did not distract from the clothes. One of my favourites was the show he did with those huge tulips which should have distracted but they worked with the clothes so beautifully.” Knowing that balance, that was Michael’s skill.

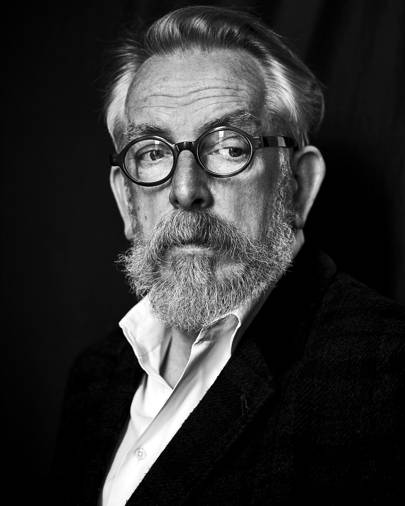

Michael literally saw the world from another perspective, another point of view. He was a striking figure in the artistic landscape at 6ft 7in. He was a giant of a man, but he did not shy away from this. In fact, he enhanced it. He insisted on wearing pointy shoes which only elongated his already large, but also very elegant, feet. Whilst working on a film in Spain he was fitted for a matador outfit. The Spanish tailor had to get a step ladder to measure him from the shoulder. He also ordered a cape in purple. He was very physical and despite his size knew how to move with dexterity, and was the best dancer I know. Kitty Arden remembers that he would show the models how to sashay properly before many of the Galliano shows. He was particularly good at showing the models how to walk up the stairs. “At the first Galliano show at the L’Opera in Paris there was a huge staircase, I remember he showed the girls how to walk up a giant set of stairs. He would do a twirl at the corner, look back at the audience, slowly put his hand on his waist and tilt his head as if he was wearing a hat. It was genius. He knew how to work a room.”

Some of the most memorable parties of the last 30 years were orchestrated by Michael. He started when he was a student at Camberwell. Fi Cotter Craig remembers going to one of Michael’s parties when they both lived in Coleherne Court in the ‘80s. “Michael was the most glamorous person I had ever met. I walked into his flat and there was a horse at his party. A grey horse. I think the horse stayed all night. They had to get it out the following morning.” Michael was at the vanguard of big party fantasia that emerged in the early ‘80s. “He brought the great outdoors into tents, ballrooms and stately homes with foraged materials which he organically grew into set pieces of pure genius. It was Blue Peter on acid with a touch of Narnia too,” says Totty Lowther, another old friend and collaborator. “No one can deny he wasn’t a fucking genius,” says Camilla Lowther, another old friend and for many years his agent. “I don’t think there are many people like that anymore. This digital age doesn’t allow it. He was utterly ambidextrous and complete in his talent.”

One of his most profound collaborations was with his great friend Mark Baldwin, artistic director of the Rambert Company. Over a period of 20 years they worked together. “Michael was a brilliant designer. A visionary. He was a stickler for detail, the right shape, the right shade. The music was the plot. Michael sought atmosphere and loved movement. He made me laugh like no other. He loved people, he loved ideas.”

Michael literally saw the world from another perspective, another point of view. He was a striking figure in the artistic landscape at 6ft 7in. He was a giant of a man, but he did not shy away from this. In fact, he enhanced it. He insisted on wearing pointy shoes which only elongated his already large, but also very elegant, feet. Whilst working on a film in Spain he was fitted for a matador outfit. The Spanish tailor had to get a step ladder to measure him from the shoulder. He also ordered a cape in purple. He was very physical and despite his size knew how to move with dexterity, and was the best dancer I know. Kitty Arden remembers that he would show the models how to sashay properly before many of the Galliano shows. He was particularly good at showing the models how to walk up the stairs. “At the first Galliano show at the L’Opera in Paris there was a huge staircase, I remember he showed the girls how to walk up a giant set of stairs. He would do a twirl at the corner, look back at the audience, slowly put his hand on his waist and tilt his head as if he was wearing a hat. It was genius. He knew how to work a room.”

Some of the most memorable parties of the last 30 years were orchestrated by Michael. He started when he was a student at Camberwell. Fi Cotter Craig remembers going to one of Michael’s parties when they both lived in Coleherne Court in the ‘80s. “Michael was the most glamorous person I had ever met. I walked into his flat and there was a horse at his party. A grey horse. I think the horse stayed all night. They had to get it out the following morning.” Michael was at the vanguard of big party fantasia that emerged in the early ‘80s. “He brought the great outdoors into tents, ballrooms and stately homes with foraged materials which he organically grew into set pieces of pure genius. It was Blue Peter on acid with a touch of Narnia too,” says Totty Lowther, another old friend and collaborator. “No one can deny he wasn’t a fucking genius,” says Camilla Lowther, another old friend and for many years his agent. “I don’t think there are many people like that anymore. This digital age doesn’t allow it. He was utterly ambidextrous and complete in his talent.”

One of his most profound collaborations was with his great friend Mark Baldwin, artistic director of the Rambert Company. Over a period of 20 years they worked together. “Michael was a brilliant designer. A visionary. He was a stickler for detail, the right shape, the right shade. The music was the plot. Michael sought atmosphere and loved movement. He made me laugh like no other. He loved people, he loved ideas.”

Michael’s work in television culminated in the work he did on Victoria. He built a wing of Buckingham Palace in an air craft carrier near Leeds. He used 2,5000 sheets of mdf for the floors and walls then 16 miles of two by two timber for the flat structures and braces. Michael was in his element. “I took this shot and sent it to Michael a couple of weeks ago,” said Jenna Coleman, who plays Queen Victoria. The photograph is of a room in the palace which Michael made. “The chandeliers are down, which seems so fitting now. Michael was a graceful, glorious, gentle giant. A creative genius, with a supreme eye and a twinkling wit. A palace created from walnuts and hand-sourced sea shells. Truly, there wasn’t a day you walked on set without being awed by him. The shining star of Victoria. You are one of a kind Michael and how we shall miss you so.”

No comments:

Post a Comment