But the appetite for a film was there. When Bonhôte (producer and co-director) and Ettedgui (writer and co-director) proposed their concept to a series of distributors in February 2017, it was financed within three days. “We wanted to make a really respectful cinematic version of Lee’s story,” Bonhôte tells Vogue. “You could go very tabloid and sensationalist, but we wanted to put his work at the film’s centre, and to try to tell his life from the fashion shows. People were excited about this.”

They took on the project, as Ettedgui says, with “zero access and zero original archive at our fingertips” and worked 18-20 hour days for a year to shape a piece of cinema that would “immerse viewers in the passion and the energy of McQueen, and the journey that his inner circle went on with him.” The stress, toil and tears it took to produce the film before a competitor’s scripted, dramatised version of McQueen’s life paid off. The profile that will come to light on the June 8 release date is, as Vogue international editor Suzy Menkes said, “the most sensitive vision about a creative who never lost his rough edges, and who put his life – the bloody history of distant warriors in Scotland and childhood abuse within his family – on stage.”

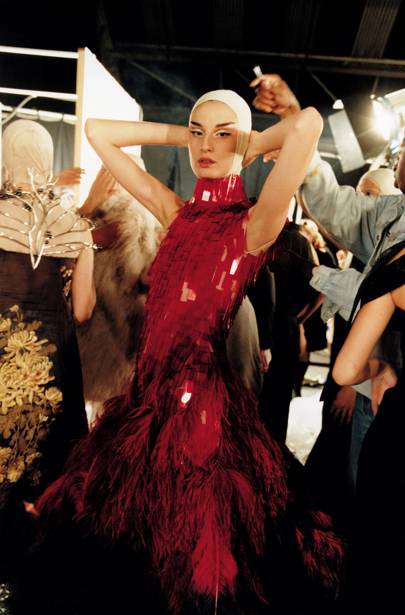

The documentary spans the breadth of McQueen’s career, from his graduation from Central Saint Martins in 1992, to his appointment as the bad boy creative director of Givenchy in 1997, his departure from the French couture house in 2001 and the final years he dedicated to his eponymous label before his suicide. The film's 111 minutes are chock full of captivating footage of his catwalk shows, from early collections, such as The Birds, to the later Plato’s Atlantis, and is interspersed with arresting, graphics of his signature skull motif. But it’s the close-up footage of his colleagues and friends recounting their personal stories with their eyes flickering with emotion that stays with the viewer as the sad story comes to a close.

The interviews, which lasted between two to four hours in each participant's home, were “never easy,” Bonhôte muses. “You have to give some of yourself because they give a lot to you. You have to be conscious, caring and accept that responsibility – I think I underestimated that, it sucked a lot of energy out of me.”

The time they spent with Rebecca Barton, a designer with whom McQueen attended Central Saint Martins, hammered home this need for the utmost respect when filming. “Rebecca was very, very close to him, and when we got to the moment where we asked her how she learned about his passing and the suicide, she just lost it completely,” Ettedgui recalls. “And she really didn't want to lose it.” Others held it together on camera, and burst into tears once it had stopped rolling.

“When you tell the story of someone that lived, you tell the story of the people that lived next to him, it's their story as much as the person’s,” Bonhôte explains. “It is actually still one of the best chapters in his life.”

The documentary spans the breadth of McQueen’s career, from his graduation from Central Saint Martins in 1992, to his appointment as the bad boy creative director of Givenchy in 1997, his departure from the French couture house in 2001 and the final years he dedicated to his eponymous label before his suicide. The film's 111 minutes are chock full of captivating footage of his catwalk shows, from early collections, such as The Birds, to the later Plato’s Atlantis, and is interspersed with arresting, graphics of his signature skull motif. But it’s the close-up footage of his colleagues and friends recounting their personal stories with their eyes flickering with emotion that stays with the viewer as the sad story comes to a close.

The interviews, which lasted between two to four hours in each participant's home, were “never easy,” Bonhôte muses. “You have to give some of yourself because they give a lot to you. You have to be conscious, caring and accept that responsibility – I think I underestimated that, it sucked a lot of energy out of me.”

The time they spent with Rebecca Barton, a designer with whom McQueen attended Central Saint Martins, hammered home this need for the utmost respect when filming. “Rebecca was very, very close to him, and when we got to the moment where we asked her how she learned about his passing and the suicide, she just lost it completely,” Ettedgui recalls. “And she really didn't want to lose it.” Others held it together on camera, and burst into tears once it had stopped rolling.

“When you tell the story of someone that lived, you tell the story of the people that lived next to him, it's their story as much as the person’s,” Bonhôte explains. “It is actually still one of the best chapters in his life.”

The home video footage that Sebastian Pons, McQueen’s former assistant, supplied was another turning point in Bonhôte and Ettedgui’s journey unravelling the personality of McQueen. Having trawled through 200 film and audio archives, suddenly they had “four hours of Lee talking and opening his heart, Lee himself talking about drugs, and a lot of other issues,” Bonhôte says. “It was very important for us that the really sensitive themes and issues were presented through his mouth. Because anyone can criticise the film, but we can always say that we had the stamp of approval from Lee himself.”

The family, who Bonhôte and Ettedgui kept in the loop throughout the filming process, finally relented, and Janet, McQueen’s sister, and Gary, his nephew, agreed to be interviewed. “The more people we spoke to, the more the family realised that we weren’t just two schmucks and that we knew what we were talking about,” Bonhôte asserts. “But when they conveyed the story, it felt like it was happening in present tense again. They were reliving everything that they went through,” Ettedgui adds. “We thought that eight years was long enough for people to want to talk about it, but we realised that it is still very, very fresh in people's memory.”

When they recently showed McQueen’s family the final edit, they loved it. “They were so thrilled because I think their worry was that it was going to show a side of Lee that they feel embarrassed about. They were really happy that we chose to show his work and not the gay clubs and all of that,” Ettedgui notes.

The duo also felt that they had stayed true to their own memories of McQueen. Bonhôte used to shoot club visuals at The Blue Note club near McQueen’s basement studio in the Seventies, and watched Isabella Blow and Katy England's gang entering and exiting. “Lee was in the middle of the creative scene when the underground art, magazine and club culture was exploding,” he remembers. Ettedgui’s father, meanwhile, was Joseph founder, Joseph Ettedgui. “I remember Isabella [Blow] actually dragged him rather forcibly to The Birds show. Even though he was a tailor, he was interested in the punk rebel story.”

No comments:

Post a Comment