And that was even before the #metoo dam had burst; or British women had woken up to the news that female BBC staff are paid, on average, nine per cent less than their male counterparts; or that, for women in their twenties, the gender pay gap has "significantly grown" in the past six years, according to data released by the Fawcett Society.

As the lids are blown off in all directions on sexual harassment, racial injustice, gender pay inequality, the rolling back of women's rights, the gap between rich and poor - and a zillion other issues, daily - how is the way we dress at all relevant?

Perhaps the only good news at a time when so many political issues are hitting home is that we're now living in an atmosphere vibrating with the possibility of change. Fashion (or clothing; we can debate what we should call it) isn't on the sidelines in this: it's a constant ally in times of trouble, a medium open to infinite nuances of meaning in the hands of ingenious people to show their beliefs. "The more we are seen, the more we are heard": no one has put it better recently than the women who came up with the idea for the Pink Pussy Hat. The words are emblazoned on Pussyhatproject.com, which got women all over the world knitting up that brilliant retort to Donald Trump's gross, sexist "Grab them by the pussy" remark as a global - cheerful - symbol of feminist defiance.

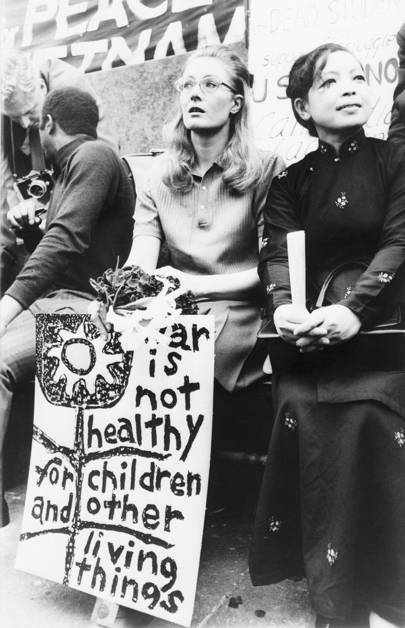

In the space of little over a year since Trump's election, the subversive possibilities of visual communication in clothing have unleashed an astonishing, uplifting, do-it-yourselves level of creativity. The like hasn't been seen since the marches and protests of the youth uprisings of 1968 - the revolution that swept from San Francisco to Paris and London 50 years ago, and a generation that dressed to change the world in tight polonecks, flares, minis and duffel coats.

What's fascinating now is seeing how high fashion and the simple, democratic - even no-cost - gestures of street protest are moving along in the same direction in the age of social media. Layers of the history of past movements are liberally cross-coded to take on the punch of new relevance. Look around right now and you'll see one very obvious example echoing the spirit of the 1960s and 1970s: the beret. The irrevocable symbol of the Black Panthers movement is out there and totally fashionable again, thanks to Beyoncé's sizzling channelling of the Panther's uniform on her Angela-Davis-afro-haired feminist dancers at the Superbowl in February 2016 - visual imagery played against the backdrop of the Black Lives Matter movement. A few months later Maria Grazia Chiuri(another fashion feminist-in-chief) put leather berets designed by Stephen Jones with every look on her Dior catwalk. "Suddenly, it was the balance and counterpoint to the clothes," Jones remembers. "She saw it could look like an army of strong, independent women, on their way."

Anyone can pick up a beret for next to nothing and wear it with the same impact as Beyoncé or the Dior models - or just as an on-trend accessory. It's textbook radical fashion practice that ideas should be open-access - that anyone can use the templates as they wish.

What's fascinating now is seeing how high fashion and the simple, democratic - even no-cost - gestures of street protest are moving along in the same direction in the age of social media. Layers of the history of past movements are liberally cross-coded to take on the punch of new relevance. Look around right now and you'll see one very obvious example echoing the spirit of the 1960s and 1970s: the beret. The irrevocable symbol of the Black Panthers movement is out there and totally fashionable again, thanks to Beyoncé's sizzling channelling of the Panther's uniform on her Angela-Davis-afro-haired feminist dancers at the Superbowl in February 2016 - visual imagery played against the backdrop of the Black Lives Matter movement. A few months later Maria Grazia Chiuri(another fashion feminist-in-chief) put leather berets designed by Stephen Jones with every look on her Dior catwalk. "Suddenly, it was the balance and counterpoint to the clothes," Jones remembers. "She saw it could look like an army of strong, independent women, on their way."

Anyone can pick up a beret for next to nothing and wear it with the same impact as Beyoncé or the Dior models - or just as an on-trend accessory. It's textbook radical fashion practice that ideas should be open-access - that anyone can use the templates as they wish.

What's so often forgotten is that there's always somebody who actually designed the symbol or had the creative brainwave of assigning a meaning to a look. Go back to the bold slogan T-shirt graphics, for a start - they were forged by the original anti-war eco-warrior designer-campaigner, Katherine Hamnett. The peace symbol - horrendously back in currency as thermonuclear war threatens - was designed by RCA graduate Gerald Holtom for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in 1958. The Gay Pride rainbow - cemented forever as the symbol for LGBTQ identities - was designed by American artist Gilbert Baker in 1978. Who knew?A powerful wordless image can have truly global impact

Hamnett is back again, with her "Cancel Brexit" T-shirt campaign, and reissuing her sustainably sourced cottonBrexit and silk designs from the 1980s through her website. The story of how she made the anti-nuclear-missile "58 per cent don't want Pershing" T-shirt, with which she confronted Mrs Thatcher at Downing Street reception in 1984, is a priceless piece of fashion history. She made it on the day. "I did think it was an opportunity, I suppose. I wasn't going to go until I decided that afternoon. I thought, what are the punchiest graphics? I was passing a newsstand, saw a billboard for The Sun, and thought: that's it! There was no Snappy Snaps or anything where you could get T-shirts done. So I did the lettering, got it exposed on to linen graphics paper, and stitched it on to a silk T-shirt."

Hamnett opened her jacket as she shook the prime minister's hand; the cameras went crazy, and one of the most indelible and forever-copied radical fashion statements in history was made. "The thing is to make the words so big, you can't not see them, you've had it. The words are inside your brain." In one way, it didn't quite play as she'd planned with Mrs Thatcher. "She bent over, read it and squawked," Hamnett laughs. "Then, quick as a flash, she said, 'We haven't got Pershing here, we've got cruise. You must be at the wrong party, dear.'"

Hamnett is back again, with her "Cancel Brexit" T-shirt campaign, and reissuing her sustainably sourced cottonBrexit and silk designs from the 1980s through her website. The story of how she made the anti-nuclear-missile "58 per cent don't want Pershing" T-shirt, with which she confronted Mrs Thatcher at Downing Street reception in 1984, is a priceless piece of fashion history. She made it on the day. "I did think it was an opportunity, I suppose. I wasn't going to go until I decided that afternoon. I thought, what are the punchiest graphics? I was passing a newsstand, saw a billboard for The Sun, and thought: that's it! There was no Snappy Snaps or anything where you could get T-shirts done. So I did the lettering, got it exposed on to linen graphics paper, and stitched it on to a silk T-shirt."

Hamnett opened her jacket as she shook the prime minister's hand; the cameras went crazy, and one of the most indelible and forever-copied radical fashion statements in history was made. "The thing is to make the words so big, you can't not see them, you've had it. The words are inside your brain." In one way, it didn't quite play as she'd planned with Mrs Thatcher. "She bent over, read it and squawked," Hamnett laughs. "Then, quick as a flash, she said, 'We haven't got Pershing here, we've got cruise. You must be at the wrong party, dear.'"

Today, when every phrase is instantly dissected on social media, it would be impossible to get away with such an inaccuracy. On the other hand, a powerful wordless image can have truly global impact when encoded in clothes, a strategy that is being ever more brilliantly put to use by young activists. Once seen, never forgotten: the protest of a group of Latina girls on the steps of a town hall in Texas, who stood wearing their traditional quinceañera 15th-birthday gowns and sashes, drawing worldwide attention to Donald Trump's ruthless deportation legislation. Other young women have haunted American senate buildings where anti-abortion legislation is being heard, filing in silently to occupy empty rows of seats dressed in the red robes and white bonnets of The Handmaid's Tale.

They are, of course, only following in the honourable tradition set over a century ago by the suffragettes, who harnessed fashion, and the meaning of colour, as methods of communication in the early days of photography. In 1980, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence devised the scheme of purple for dignity, white for purity and green for hope - branding for the cause, which triggered Liberty and Selfridges to start selling ranges of tricolour ribbon, underwear, bags and soap. Christina Broom, considered Fleet Street's first woman photographer, documented marches of thousands of suffragists and suffragettes wearing white dresses designed to prove to the country the dignity of their cause.

They are, of course, only following in the honourable tradition set over a century ago by the suffragettes, who harnessed fashion, and the meaning of colour, as methods of communication in the early days of photography. In 1980, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence devised the scheme of purple for dignity, white for purity and green for hope - branding for the cause, which triggered Liberty and Selfridges to start selling ranges of tricolour ribbon, underwear, bags and soap. Christina Broom, considered Fleet Street's first woman photographer, documented marches of thousands of suffragists and suffragettes wearing white dresses designed to prove to the country the dignity of their cause.

"Same shit, different century", read a beautifully hand-painted placard in art nouveau script which was waved by three young women dressed in historically accurate suffragette outfits at the Women's March in London last year. As far as women's rights are concerned, there are generations - daughters and mothers (women in their fifties are even worse off, in comparison to men) - who are now realising the extent of the unfinished business left by the suffragettes, and by the first waves of feminism. Can what we wear change anything for the better? Of course not: only fighting to legislate for true transparency and gender parity can do that. But in the meantime, fashion can be a powerful ally as we set out, dressed to protest.

No comments:

Post a Comment