But even as the selection of brands available in China broadens, there is another major factor driving Wang’s decision to do much of her shopping abroad. “I find some things in Shanghai, but the price is too high including tax,” she said. “I’d rather buy them abroad and ship them back to China.” Wang certainly isn’t alone. Exane BNP Paribas estimates that travellers account for about 50 percent of global luxury goods sales.

Of course, the Internet has made it easier than ever to comparison shop across every region of the world and find the best prices. “They’re shopping with a smartphone and receiving the information in symmetry,” said David Zhao, founder and chief executive of Chinese multi-brand e-commerce site Shangpin, which sells labels like Alexander Wang and Stuart Weitzman. “People don’t want to be treated as idiots.”

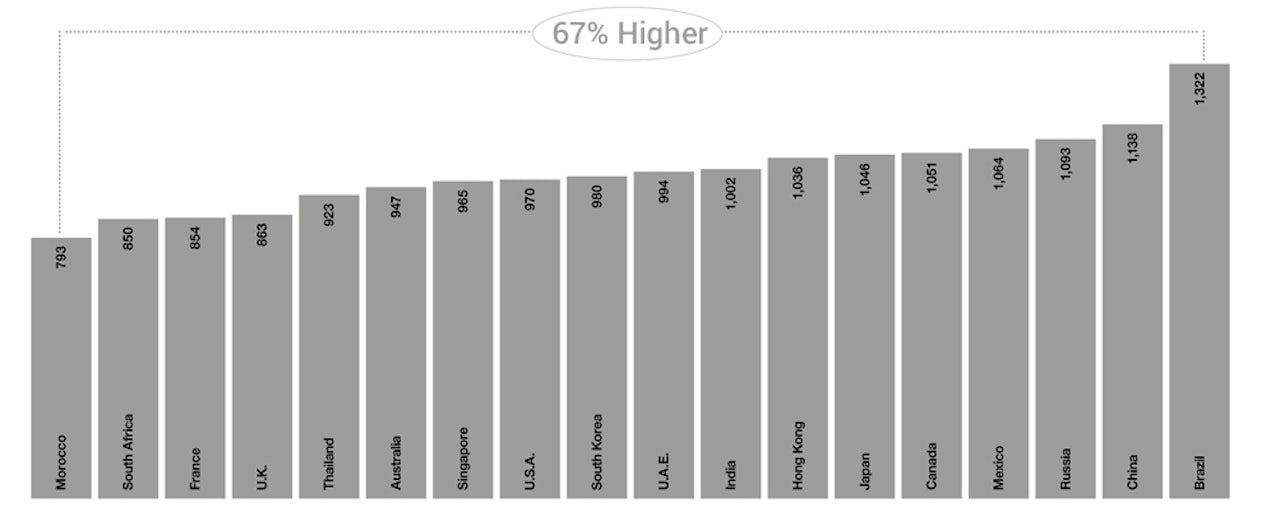

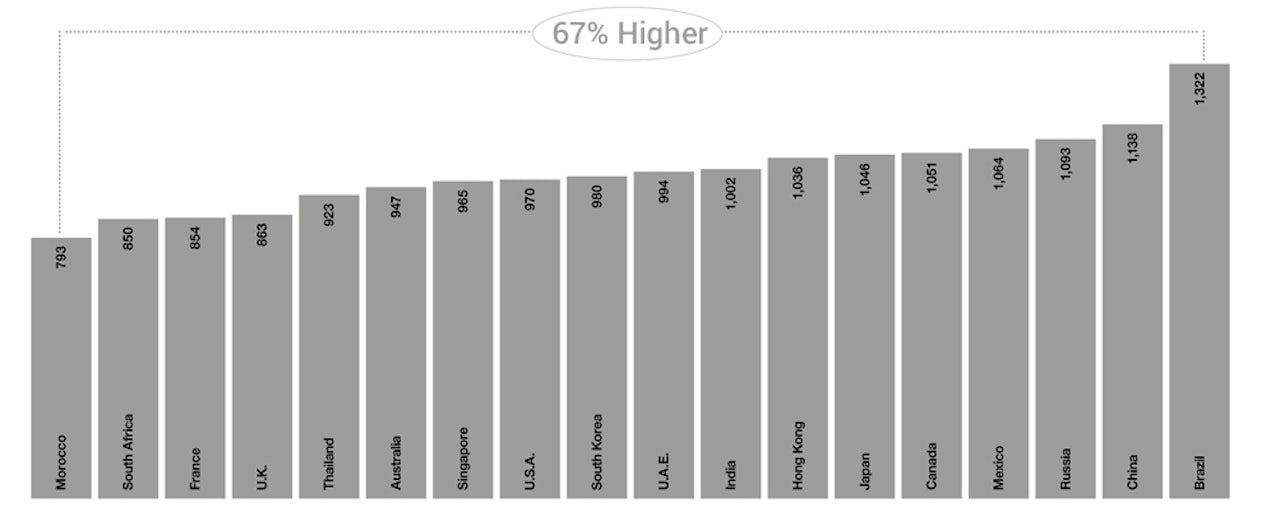

On Louis Vuitton’s e-commerce site, simply clicking on the “change location” button quickly reveals how the same item is priced differently in different markets. Vuitton’s monogrammed Speedy 30 bag retails for €760 in France, or about $854 at current exchange rates. In the United Kingdom, the price is about the same: $863. But the further one travels from Europe, the pricier the bag becomes. In the United States, the price is $970, a 12 percent markup. In Japan, it’s $1,046, a 21 percent hike. In China, it’s $1,138, or 32 percent more expensive. In Brazil, the same Speedy 30 costs a whopping 53 percent more at $1,322.

Meanwhile, Bottega Veneta’s classic intrecciato shoulder bag costs $2,550 in the United States, $2,600 in Europe, $2,936 in Hong Kong and $3,073 in Japan. Not as wide a range, but enough to make a difference to price-conscious consumers.

Global transparency of prices is an industry game changer. Massive tourist dollars moving from one continent to another, just for bargaining in luxury, means that 2016 has been an earthquake, pricing-wise.

Exchange rates — in particular, a weak euro and a weak yen — have made pricing differences between some regions even more pronounced. But currency fluctuation is only one of the factors at play here. Local taxes play a major role — especially in China and Brazil, where imports valued up to $3,000 are slapped with a tax of 60 percent. What’s more, some brands have traditionally charged higher prices in international markets where they believe consumers will pay.

There can often be as much as a 60 to 70 percent pricing delta from Europe to China, according to consulting firm Bain & Co. “Global transparency of prices is an industry game changer,” said Federica Levato, a partner at Bain. “Massive tourist dollars moving from one continent to another, just for bargaining in luxury, means that 2016 has been an earthquake, pricing-wise.”

Of course, there is emotional value to shopping away from home. While the strength of the American dollar has made it slightly less attractive for those in Mexico, for instance, to cross the border for shopping trips, there is still a sense of pride that comes with buying something in the US. “Plus, if you go to Liverpool [department store] in Mexico City, you just can’t compare the experience to something like Barneys,” said Fflur Roberts, an analyst at Euromonitor International. “Shopping abroad will always be aspirational. It’s far more attractive for someone who lives in Mexico City to fly to New York and shop on Fifth Avenue, regardless of what they can buy at home.”

Prices of Louis Vuitton Speedy 30 Bag Around the World (USD)

The pull is even stronger in Europe, home to many top luxury brands. “It’s authenticity, it’s experience, it’s the fact that if I buy a handbag for my sister at Chanel in Paris, that’s worth a lot more than having bought it in China,” said Philip Guarino, director at China Luxury Advisors. Shoppers in emerging markets also feel like they’re being sidelined when it comes to product selection. “People will say that they’re convinced there is more variety elsewhere than what’s presented on the shelves in China,” Guarino adds.However, price plays a major role.

In China alone, 81 percent of consumers planning a holiday abroad intend to shop while vacationing, according to a recent report released by Global Blue, a tax-free shopping company, which tracked 27 million tax-free shopping transactions and surveyed 5,000 Chinese travellers for the study. To be sure, a significant slice of sales to travellers — about 12 to 13 percent — happen at duty-free shops at airport malls. But buying abroad is increasingly linked to underlying price differences across regions.

“In the past five or 10 years, many brands have consistently increased the prices in their product offering. An iconic bag can cost more than 2.5 times what it cost 10 years ago,” Levato explained. “This is very visible to the customer because the iconic bags don’t change. By shopping in a more affordable market, the consumer can see that they’re getting a little bit more value for what they buy. It’s a key point.”

Indeed, for those eager to pay less for luxury goods, the difference in price between shopping in Europe and shopping at home can easily offset the cost of a flight and a few nights in a hotel (especially when factoring in value added tax (VAT) return, which can range from 17 percent to 27 percent).

Then there are those who turn to grey market shopping agents, known in China as daigou, who procure goods from abroad at lower prices. These agents charge a fee, of course, but the price difference is great enough for the transaction to be worthwhile for both parties. Daigou accounted for $7.6 billion in sales in 2015, according to Bain.

For luxury brands, the impact of increased pricing transparency can carry financial burden. For the past decade, major luxury players — including Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Burberry and Zegna — have opened dozens of stores in local markets like Brazil and Russia. But nowhere so aggressively as China, where new wealth creation has driven impressive demand for luxury brands in recent years, making it a key market. Mainland China is home to 890,000 high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) — up from 760,000 the previous year — with a combined wealth of $4.5 trillion, according to Capgemini’s 2015 World Wealth Report.

But the sheer number of Chinese consumers now shopping abroad has forced many major luxury brands to reconsider their local retail networks. According to a report from Bain, Louis Vuitton closed four stores in China in 2015, and opened one. Zegna closed four stores and opened zero. Gucci closed five stores and opened one. Burberry closed two and opened zero. Bottega Veneta closed six and opened two.

They’re shopping with a smartphone and receiving the information in symmetry. People don’t want to be treated as idiots.

The Chinese government’s crackdown on gifting, which began in 2013, has also contributed to the woes. What’s more, it’s extremely expensive to operate stores in China. “In China, retail rents are very high, which means [brands] need to keep enough of a markup to offset the costs of renting,” Shangpin’s Zhao explained. “They need to think about lifetime growth, and whether bringing a brand into a new country will [eventually] result in a return on investment. It’s a difficult decision to make.”

And yet, tapping international markets is vital to the health of luxury brands, which can’t rely on Europe’s more affordable prices to make up for losses abroad. While many makers of luxury goods were buoyed by European tourism, consumption has slowed in the first half of 2016, in part because of the terrorist attacks in Paris and Belgium. Indeed, Global Blue reported that Chinese tax—free shopping dropped in March 2016, falling 24 percent from the previous year.

There’s more. In April 2016, the Chinese government increased fees on packages shipped from abroad, and vowed to tighten custom controls so that those working in the grey market will have a more difficult time bringing large quantities of luxury goods into the country. For instance, tariffs on watches ordered from overseas businesses jumped to 60 percent, up from 30 percent. Jewellery taxes rose to 15 percent from 10 percent. New laws have also made it more difficult for those travelling abroad to withdraw large wads of cash with their UnionPay cards. While the lines of Chinese tourists gripping euros outside Louis Vuitton in Paris are unlikely to disappear completely, how much cash they’re holding may decrease. Starting in January 2016, the annual UnionPay limit on cash withdrawals abroad was reduced to 100,000 yuan (about $15,328).

So how are brands adapting?

Some are harmonising their global pricing. In 2015, Chanel announced that it would adjust its prices to make them even across markets, enticing consumers to shop locally. Chanel’s quilted flap bag, for instance, costs $4,800 euros in Paris at current exchange rates, $4,900 in New York and $4,567 in Beijing. “Last year, in 2015, we did something really strong for our customers. We harmonised our prices everywhere in the world except in Brazil — for customs reasons — but we did that in China. That’s important because that’s a very strong sign we give to the customers. We are building the brand for the next 20 years, not for the past 20 years,” Bruno Pavlovsky, Chanel’s president of fashion, told BoF on a recent trip to China. “At the moment we’re quite happy with China. With double-digit growth, our customer base is growing, our boutique business is growing, and I think that the brand is quite well perceived by the Chinese customers.”

Others take a more straightforward approach. For example, Hermès says it will not adjust prices so that they are even in every markets. However, the company does not raise prices in markets where it believes consumers will pay more, either. “We don’t have a strategy of price; we don’t use pricing as a marketing tool,” Hermès chief executive Axel Dumas told BoF in November 2015. “Our price reflects the cost of production, the manufacturing costs. It’s important that the price reflects the reality… We are not proposing a new country where we invest a lot and discount the other one. We always try to have a balanced way of investing.”

“If you price a collection with an Excel spreadsheet only looking about spread and the currency exchange, you’re never going to be successful because the consumer is going to be dragged by that,” said Yves Saint Laurent chief executive Francesca Bellettini in an exclusive interview with BoF in April. “What I believe is that first of all you need to price your collection relevant for the market and with the perfect balance of value for money. Consumers don’t want to be fooled around anymore. There is always going to be exchange rates and there is always going to be travelling. There is also a consumer that likes to bargain when they travel, by culture and by definition. So given that places are different, a little bit of spread is healthy.”

For some brands — especially accessible luxury brands, like Tory Burch — who operate in still-new markets like China with local franchise partners, controlling prices is much more difficult. “It’s easier for someone like Chanel to balance prices because they directly own their stores,” Zhao said. “They control everything.” As a wholesale partner to many aspirational and high-end brands, Zhao works with his Western counterparts to offer more reasonable prices via Shangpin, whose customer base shops 82 percent of the time on mobile.

But for those who harmonise prices across the world, how often should it happen? Once yearly, twice yearly, once a week or day-by-day, like the price of oil? For luxury brands that operate through their own channels with zero wholesale or franchise partners, this isn’t out of the question. Eschewing physical price tags — either by forcing the consumer to interact with the sales associate or installing a price-check kiosk in each outpost — would allow for dynamic pricing, although it wouldn’t necessarily fix things. Says Levato, “There is no secret recipe that will work for every brand.”

Meanwhile, Bottega Veneta’s classic intrecciato shoulder bag costs $2,550 in the United States, $2,600 in Europe, $2,936 in Hong Kong and $3,073 in Japan. Not as wide a range, but enough to make a difference to price-conscious consumers.

Global transparency of prices is an industry game changer. Massive tourist dollars moving from one continent to another, just for bargaining in luxury, means that 2016 has been an earthquake, pricing-wise.

Exchange rates — in particular, a weak euro and a weak yen — have made pricing differences between some regions even more pronounced. But currency fluctuation is only one of the factors at play here. Local taxes play a major role — especially in China and Brazil, where imports valued up to $3,000 are slapped with a tax of 60 percent. What’s more, some brands have traditionally charged higher prices in international markets where they believe consumers will pay.

There can often be as much as a 60 to 70 percent pricing delta from Europe to China, according to consulting firm Bain & Co. “Global transparency of prices is an industry game changer,” said Federica Levato, a partner at Bain. “Massive tourist dollars moving from one continent to another, just for bargaining in luxury, means that 2016 has been an earthquake, pricing-wise.”

Of course, there is emotional value to shopping away from home. While the strength of the American dollar has made it slightly less attractive for those in Mexico, for instance, to cross the border for shopping trips, there is still a sense of pride that comes with buying something in the US. “Plus, if you go to Liverpool [department store] in Mexico City, you just can’t compare the experience to something like Barneys,” said Fflur Roberts, an analyst at Euromonitor International. “Shopping abroad will always be aspirational. It’s far more attractive for someone who lives in Mexico City to fly to New York and shop on Fifth Avenue, regardless of what they can buy at home.”

Prices of Louis Vuitton Speedy 30 Bag Around the World (USD)

The pull is even stronger in Europe, home to many top luxury brands. “It’s authenticity, it’s experience, it’s the fact that if I buy a handbag for my sister at Chanel in Paris, that’s worth a lot more than having bought it in China,” said Philip Guarino, director at China Luxury Advisors. Shoppers in emerging markets also feel like they’re being sidelined when it comes to product selection. “People will say that they’re convinced there is more variety elsewhere than what’s presented on the shelves in China,” Guarino adds.However, price plays a major role.

In China alone, 81 percent of consumers planning a holiday abroad intend to shop while vacationing, according to a recent report released by Global Blue, a tax-free shopping company, which tracked 27 million tax-free shopping transactions and surveyed 5,000 Chinese travellers for the study. To be sure, a significant slice of sales to travellers — about 12 to 13 percent — happen at duty-free shops at airport malls. But buying abroad is increasingly linked to underlying price differences across regions.

“In the past five or 10 years, many brands have consistently increased the prices in their product offering. An iconic bag can cost more than 2.5 times what it cost 10 years ago,” Levato explained. “This is very visible to the customer because the iconic bags don’t change. By shopping in a more affordable market, the consumer can see that they’re getting a little bit more value for what they buy. It’s a key point.”

Indeed, for those eager to pay less for luxury goods, the difference in price between shopping in Europe and shopping at home can easily offset the cost of a flight and a few nights in a hotel (especially when factoring in value added tax (VAT) return, which can range from 17 percent to 27 percent).

Then there are those who turn to grey market shopping agents, known in China as daigou, who procure goods from abroad at lower prices. These agents charge a fee, of course, but the price difference is great enough for the transaction to be worthwhile for both parties. Daigou accounted for $7.6 billion in sales in 2015, according to Bain.

For luxury brands, the impact of increased pricing transparency can carry financial burden. For the past decade, major luxury players — including Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Burberry and Zegna — have opened dozens of stores in local markets like Brazil and Russia. But nowhere so aggressively as China, where new wealth creation has driven impressive demand for luxury brands in recent years, making it a key market. Mainland China is home to 890,000 high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) — up from 760,000 the previous year — with a combined wealth of $4.5 trillion, according to Capgemini’s 2015 World Wealth Report.

But the sheer number of Chinese consumers now shopping abroad has forced many major luxury brands to reconsider their local retail networks. According to a report from Bain, Louis Vuitton closed four stores in China in 2015, and opened one. Zegna closed four stores and opened zero. Gucci closed five stores and opened one. Burberry closed two and opened zero. Bottega Veneta closed six and opened two.

They’re shopping with a smartphone and receiving the information in symmetry. People don’t want to be treated as idiots.

The Chinese government’s crackdown on gifting, which began in 2013, has also contributed to the woes. What’s more, it’s extremely expensive to operate stores in China. “In China, retail rents are very high, which means [brands] need to keep enough of a markup to offset the costs of renting,” Shangpin’s Zhao explained. “They need to think about lifetime growth, and whether bringing a brand into a new country will [eventually] result in a return on investment. It’s a difficult decision to make.”

And yet, tapping international markets is vital to the health of luxury brands, which can’t rely on Europe’s more affordable prices to make up for losses abroad. While many makers of luxury goods were buoyed by European tourism, consumption has slowed in the first half of 2016, in part because of the terrorist attacks in Paris and Belgium. Indeed, Global Blue reported that Chinese tax—free shopping dropped in March 2016, falling 24 percent from the previous year.

There’s more. In April 2016, the Chinese government increased fees on packages shipped from abroad, and vowed to tighten custom controls so that those working in the grey market will have a more difficult time bringing large quantities of luxury goods into the country. For instance, tariffs on watches ordered from overseas businesses jumped to 60 percent, up from 30 percent. Jewellery taxes rose to 15 percent from 10 percent. New laws have also made it more difficult for those travelling abroad to withdraw large wads of cash with their UnionPay cards. While the lines of Chinese tourists gripping euros outside Louis Vuitton in Paris are unlikely to disappear completely, how much cash they’re holding may decrease. Starting in January 2016, the annual UnionPay limit on cash withdrawals abroad was reduced to 100,000 yuan (about $15,328).

So how are brands adapting?

Some are harmonising their global pricing. In 2015, Chanel announced that it would adjust its prices to make them even across markets, enticing consumers to shop locally. Chanel’s quilted flap bag, for instance, costs $4,800 euros in Paris at current exchange rates, $4,900 in New York and $4,567 in Beijing. “Last year, in 2015, we did something really strong for our customers. We harmonised our prices everywhere in the world except in Brazil — for customs reasons — but we did that in China. That’s important because that’s a very strong sign we give to the customers. We are building the brand for the next 20 years, not for the past 20 years,” Bruno Pavlovsky, Chanel’s president of fashion, told BoF on a recent trip to China. “At the moment we’re quite happy with China. With double-digit growth, our customer base is growing, our boutique business is growing, and I think that the brand is quite well perceived by the Chinese customers.”

Others take a more straightforward approach. For example, Hermès says it will not adjust prices so that they are even in every markets. However, the company does not raise prices in markets where it believes consumers will pay more, either. “We don’t have a strategy of price; we don’t use pricing as a marketing tool,” Hermès chief executive Axel Dumas told BoF in November 2015. “Our price reflects the cost of production, the manufacturing costs. It’s important that the price reflects the reality… We are not proposing a new country where we invest a lot and discount the other one. We always try to have a balanced way of investing.”

“If you price a collection with an Excel spreadsheet only looking about spread and the currency exchange, you’re never going to be successful because the consumer is going to be dragged by that,” said Yves Saint Laurent chief executive Francesca Bellettini in an exclusive interview with BoF in April. “What I believe is that first of all you need to price your collection relevant for the market and with the perfect balance of value for money. Consumers don’t want to be fooled around anymore. There is always going to be exchange rates and there is always going to be travelling. There is also a consumer that likes to bargain when they travel, by culture and by definition. So given that places are different, a little bit of spread is healthy.”

For some brands — especially accessible luxury brands, like Tory Burch — who operate in still-new markets like China with local franchise partners, controlling prices is much more difficult. “It’s easier for someone like Chanel to balance prices because they directly own their stores,” Zhao said. “They control everything.” As a wholesale partner to many aspirational and high-end brands, Zhao works with his Western counterparts to offer more reasonable prices via Shangpin, whose customer base shops 82 percent of the time on mobile.

But for those who harmonise prices across the world, how often should it happen? Once yearly, twice yearly, once a week or day-by-day, like the price of oil? For luxury brands that operate through their own channels with zero wholesale or franchise partners, this isn’t out of the question. Eschewing physical price tags — either by forcing the consumer to interact with the sales associate or installing a price-check kiosk in each outpost — would allow for dynamic pricing, although it wouldn’t necessarily fix things. Says Levato, “There is no secret recipe that will work for every brand.”