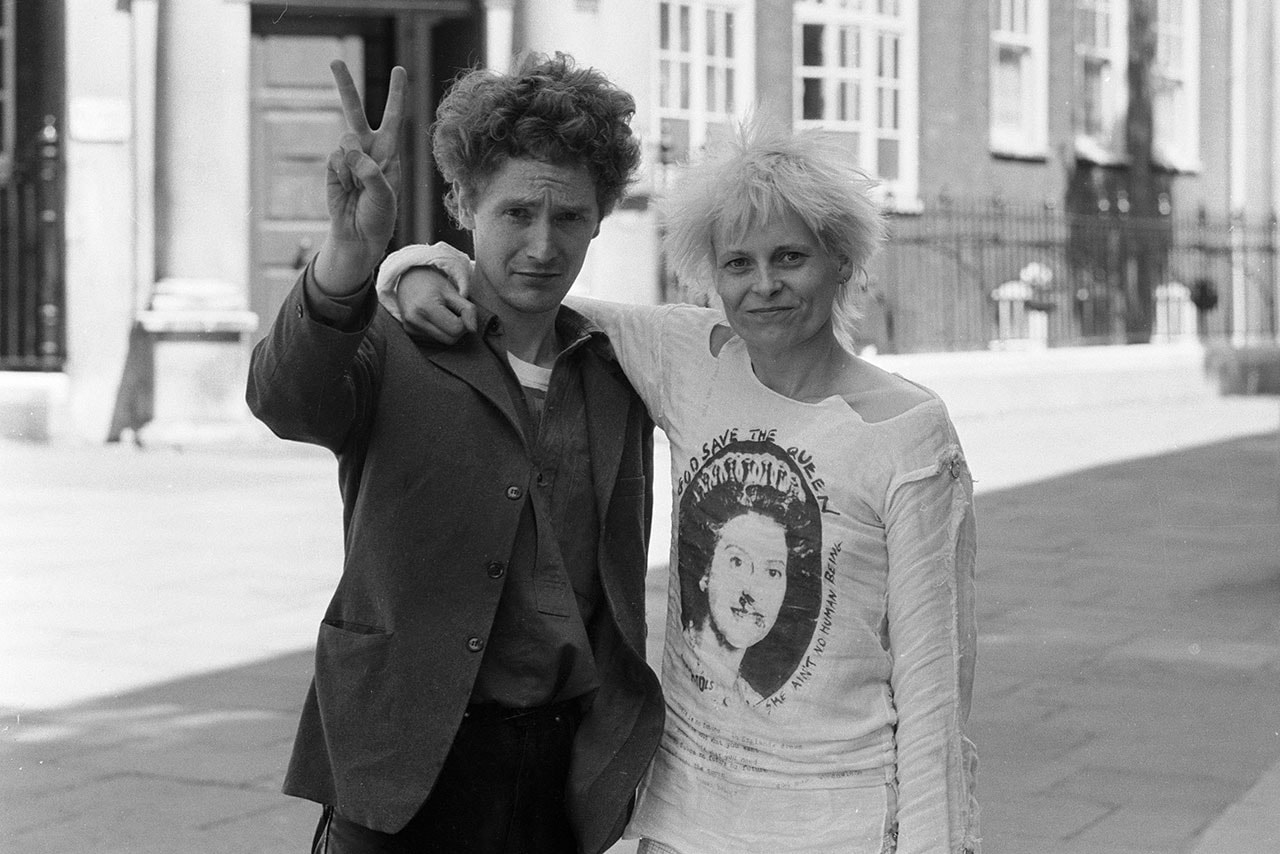

However, it’s worth starting with one key point in her history: her provocative store co-founded with Sex Pistols manager and future husband Malcolm McLaren in the mid ‘70s. SEX — eventually renamed Seditionaires, then World’s End — was where Westwood first distributed her intentionally-shoddy handmade garments, ranging from graphic tees emblazoned with breasts, swastikas and religious symbols (since referenced by countless devotees) to bondage trousers (also frequently referenced).

The influence of Westwood’s punk-era designs ran in stark contrast to the fashion industry, but their influence still reverberated throughout. For instance, Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo made their controversial Parisian debuts shortly after shopping at SEX, at least partially inspired by Westwood’s disintegrating knitwear and anti-establishment ethos. Indeed, Westwood’s Fall/Winter 1994 range showcased comically exaggerated anatomies merely three years before Kawakubo’s iconic Spring/Summer 1997 show, referred to by fans as the “Lumps and Bumps” collection.

Westwood’s same uprooting attitude fueled the subversive Ura-Hara movement, including the designs of Hiroshi Fujiwara and Jun Takahashi. years later, Westwood’s widespread influence was reaffirmed when even Dolce & Gabbana admitted to transparent imitation.

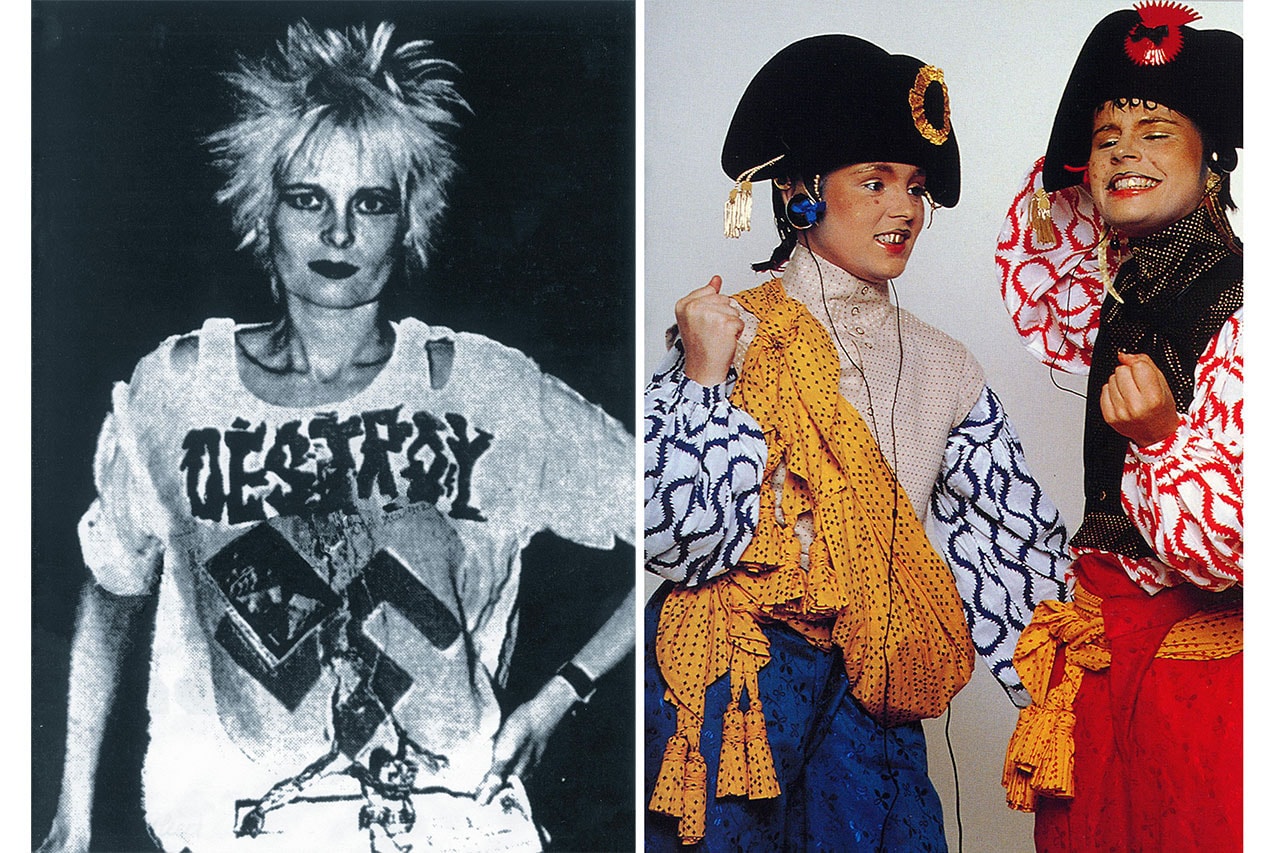

In an industry packed with legacy-hungry designers, few can claim more innovation than Westwood. Her legendary 1981 Pirates runway show predated Jean Paul Gaultier’s nautical dabbling later that decade, while her strappy, upcycled bondage trousers informed creations from the likes of Christopher Nemeth, Helmut Lang and Maison Margiela. Other inimitable creations include Westwood’s armor rings and signature rocking horse shoes — Westwood and McLaren also supported George Cox’s trademark creepers, which have since become a symbol of punk rebellion.

The visual language of punk isn’t Westwood’s alone to claim, but her skill in translating the movement’s attitude to wearables remains a lasting point of strength — what other living designer can say they effectively outfitted a musical revolution? Westwood’s take-no-prisoners attitude has never wavered, and the designer remains an activist and figure of change. Throughout the years, she’s donated to and promoted the UK’s environmentally-focused Green Party, launched Climate Revolution, publicly mocked Margaret Thatcher and and invited activists to perform during a runway show, to name a few notable acts. Westwood puts her money where her mouth is, catering to her deeply-held credo over fashion’s fickle tastes.

Though Westwood’s design acumen is far from negligible, her rebellious, headline-making designs are perhaps her best-known and most forward-looking. Prior to Westwood, designers like Pierre Cardin and Gaultier stirred up plenty controversy within the fashion system, but Westwood constantly battled conventionality and trends from the outside-in. Consider Westwood’s iconic mini-crini dress, revealed in Spring/Summer 1985 as a progressive revision of the stodgy crinoline dress, a symbol of 19th-century conservatism.

Similarly, her forward-thinking usage of tartan and Harris Tweed elevated Scotland’s traditional patterns and textiles from intentionally-unfashionable heritage into striking dresses for Fall/Winter 1987’s “Harris Tweed” collection. Or, examine her aggressive dissection of traditional fabrics for Spring/Summer 1991’s “Cut and Slash.” There, she reimagined violently-slashed fabrics of the 16th and 17th centuries in sleek satin rugged denim, predating the contemporary taste for distressed jeans.

When Pharrell wore a re-edition of Westwood’s enormous Buffalo hat, worn to the 2014 Grammys, was a dual moment of clarity. It both cemented his role as style-conscious statement-maker and affirmed Westwood’s ongoing relevance in the industry. Today, Westwood’s Harris Tweed-inspired Orb logo is nearly as recognizable as its forebear, with a new generation uncovering the British creative’s uncanny foresight and uncompromising garments. Recent collaborations with Vans skate shoes and ASICS runners have brought Westwood’s inimitable style to more approachable silhouettes, much like Westwood’s Anglomania x Lee partnerships did several years prior.

In recent years, household names have paid tribute to the world’s foremost British designer. Notably, Riccardo Tisci brought Westwood on board for a Burberry collaboration, upending traditional British staples with Westwood’s dramatic silhouettes. Ironically, with Westwood always a step ahead of the fashion industry, collectors are now looking backwards, with the Seditionaries and Anglomania designer finding new life on the secondhand market. Newfound interest from archivists has inspired the Westwood brand to reissue Orb jewelry and continue dabbling in doodled graphics — don’t be surprised when Dame Viv inevitably collaborates with a major streetwear brand, à la Gaultier x Supreme.

Andreas Kronthaler, who Westwood married in 1993, has aided the designer in bringing her namesake label into brave new frontiers since he began aiding her creative process in the ’90s; since 2016, his name has led her runway shows as a sign of his importance to the enduring Vivienne Westwood brand. However, Westwood’s legacy is hers alone, due to years of unwavering activism that cap her decades of boundary-pushing design. Climate concerns, struggles for equality and discordant fashion design all remain hot topics in the current fashion cycle, trails long-since blazed by Westwood, a patron saint for all conscious, idiosyncratic designers.

No comments:

Post a Comment